Lets Go Burn Down the Observatory So Thatll Never Happen Again

Anthony Mecke had drifted to sleep in the suspension room when a loud knock roused him at 1:23 a.g. "We but got the call," a coworker said.

Mecke, a moonfaced 45-twelvemonth-old, is the manager of systems operation preparation at CPS Energy, the city-endemic electricity provider that serves San Antonio. He started at the visitor non long after loftier schoolhouse, working at ane point equally a cablevision splicer, a job he performed in hot tunnels beneath the sidewalks of San Antonio. He thought he'd seen it all. Merely when he hustled from the break room, where he'd sneaked in a power nap after an all-solar day shift, into the visitor'south cavernous command room, housed in a tornado-proof building on the city's East Side, what he witnessed unsettled him.

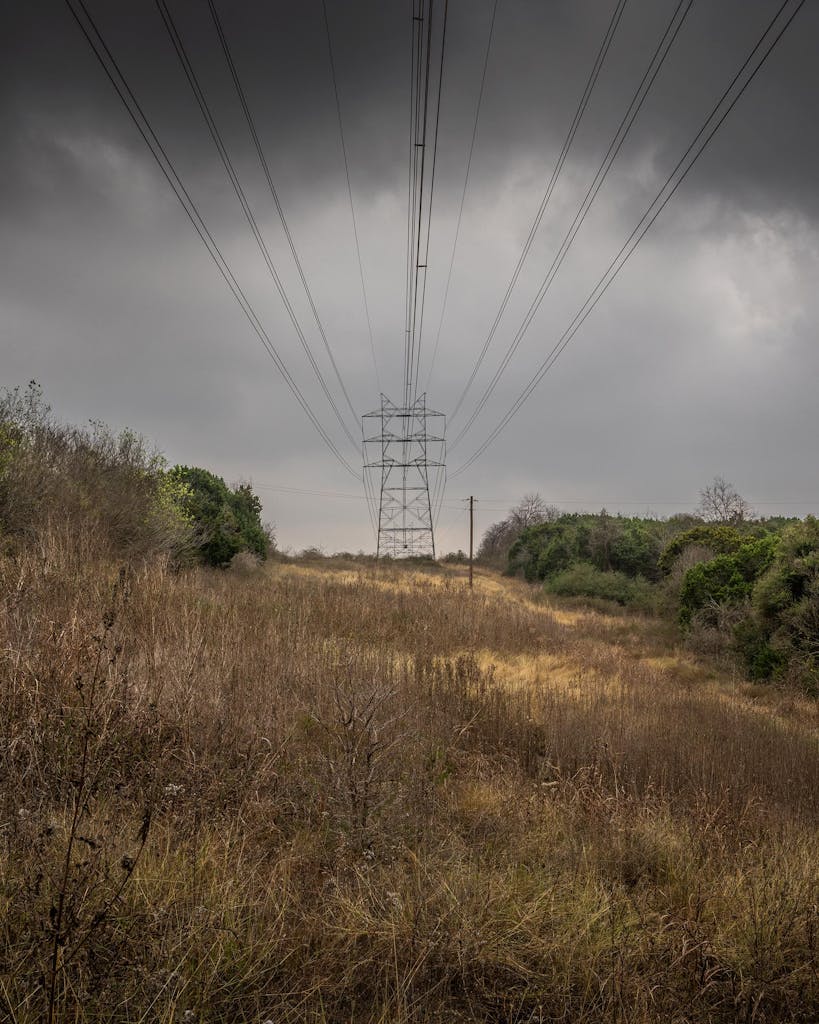

This was Monday, February 15, 2021. A winter tempest had brought unusually frigid temperatures to the entire middle swath of the Us, from the Canadian border to the Rio Grande. In San Antonio, it dropped to 9 degrees. In Fort Worth, the tempest'southward icy arrival a few days earlier had led to a 133-vehicle pileup that left 6 dead. Abilene and Pflugerville had advised residents to eddy their water, the first of thousands of such warnings that would eventually affect 17 one thousand thousand Texans. Across the country, families hunkered down and did anything they could to stay warm. The overwhelming majority of Texas homes are outfitted with electric heaters that are the technological equivalent of a toaster oven. During the well-nigh astringent common cold fronts, residents crank up those inefficient units, and some even turn on and open up electric ovens and apply hair dryers.

Mecke could track the spiking energy use in real time. I wall of the control room is covered in enormous computer monitors displaying maps and data. He scanned for one detail piece of information. The state'due south electricity reserves, which are tapped to preclude emergencies, were already depleted. The problem wasn't just surging demand. Power plants all beyond the grid were shutting off, incapacitated by frozen equipment and a dearth of natural gas, the primary source of fuel.

The Texas power grid was, at that moment, similar an airplane low on fuel that needed to jettison cargo to stay aloft. That'due south what the call had been about. The state'south filigree operator, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, or ERCOT, had but told CPS Free energy and fifteen of the country'south other electric utility companies to immediately begin turning off power for portions of their service areas. The issue would be blackouts.

Nobody all the same knew just how widespread the blackouts would get—that they would spread beyond nearly the unabridged state, leave an unprecedented eleven million Texans freezing in the night for as long equally three days, and effect in as many equally seven hundred deaths. Just neither could the governor, legislators, and regulators who are supposed to oversee the state's electric grid claim to be surprised. They had been warned repeatedly, past experts and by previous calamities—including a major blackout in 2011—that the filigree was uniquely vulnerable to common cold weather.

Unlike most other states that safely endured the February 2021 storm, Texas had stubbornly declined to crave winterization of its power plants and, just equally critically, its natural gas facilities. In large office, that's because the country's politicians and the regulators they appoint are frequently captive to the oil and gas industry, which lavishes them with millions of dollars a yr in campaign contributions. During the Feb freeze, the gas industry failed to deliver critically needed fuel, and while Texans of all stripes suffered, the gas industry scored windfall profits of nearly $11 billion—creating debts that residents and businesses will pay for at least the next decade.

Since last February, the state has appointed new regulators and tweaked some of its statutes. But despite the misery, expiry, economic disruption, and embarrassment that Texas suffered, piddling has inverse. The country remains susceptible to the threat that another winter tempest could inflict blackouts as bad as—or even worse than—last yr's catastrophe. Despite promises from public officials to rectify these problems, nosotros remain largely caught and tin only hope we aren't thrashed by some other Chill blast. Even as forecasters predict a relatively warm winter on average, there is compelling bear witness that such extreme weather phenomena are becoming more than common. To understand the danger, it'due south worth examining how close the Texas grid came last year to a meltdown that could have left much of the state without power for several weeks, or even months.

Two days before Mecke was awakened in his part, ERCOT had held an emergency conference call to warn the state'south utilities and rural electric cooperatives that blackouts were probable. ERCOT officials said the grid might have to shed as much as 7,500 megawatts—effectively darkening roughly one of every 8 homes in the land. That's virtually twice as much as the concluding controlled load shed, in 2011, when rolling blackouts had lasted as long as 8 hours, which in turn was four times longer than the previous large-scale blackout, in 2006.

The worst-case scenario ERCOT had gamed out, what it called "extreme wintertime," contemplated a tape-setting demand of 67.2 gigawatts. Electricity consumption blew past that marker at 7 p.g. on February 14. Meanwhile, electricity supply connected to dwindle as underinsulated power plants went down, 1 after another.

For the filigree to office properly, the supply of electricity must always match demand; this equilibrium is reflected in the grid's frequency, which unremarkably remains steady at threescore hertz. Power plants across the state are tuned in to the frequency, and they automatically increase or decrease generation to maintain equilibrium. The grid is like a giant synchronized machine, its components linked across hundreds of miles, from Midland to Houston, from Amarillo to Brownsville. On this night, as demand drastically outpaced supply, the frequency dropped and the vast machine began churning faster. But eventually it couldn't compensate on its own.

Past 1:23 a.chiliad., ERCOT could no longer delay activeness. An operator in its command room picked up the hotline telephone, which was wired to sixteen of the land'southward utility companies, and ordered a chiliad-megawatt load shed statewide. "Yous practice for this for years," Mecke said. "You promise it never happens."

In fact, a few hours before, he'd run his coworkers through a simulation of a most identical load shed. When the time came to carry out the operation for real, there were no hiccups. "It was surprisingly calm," he said. "It was shine." Inside seconds, electricity in parts of San Antonio began to blink off. Mecke, hopeful that the grid would stabilize, breathed a sigh of relief. The calm was short-lived.

The frequency should have risen afterward the load shed, but instead it kept falling. Information technology was "nerve-racking," said Mecke.

At ane:47 a.thou., the hotline phone rang again. Everyone in the CPS control center stopped what they were doing. ERCOT needed another thou megawatts cut. Because of coronavirus precautions, CPS executives weren't in the control room. Rudy Garza, the chief customer officer, tracked the frequency's dangerous decline on his phone, texting dorsum and forth with industry friends and former coworkers from across the state. "We were scared," he said.

CenterPoint Energy, a utility in Houston, runs a command room similar to that of CPS. Eric Easton, CenterPoint'southward vice president of existent-fourth dimension operations, was hastening to execute the second round of blackouts when the hotline phone rang for the third fourth dimension, at 1:51 a.m. ERCOT ordered another iii k megawatts—more than the first 2 combined. "Calls started coming in so fast that they were overlapping," said Easton. "When are we going to cease shedding load?" he wondered.

But the situation was only growing more dire. At the precise time of the tertiary call, the frequency reached a critical threshold: 59.4 hertz. The Texas grid, which has been effectually in some class since Earth State of war II, had only once in its history fallen this low. Automatic turbines beyond the state began spinning even faster to produce more electricity, but when the frequency dips below 59.4 hertz, the turbines attain speeds and pressures that can cause catastrophic damage to them, requiring that they exist repaired or replaced. This scenario was unlikely considering, to forestall information technology, the grid automatically triggers a nine-minute countdown when it strikes 59.4 hertz. If the frequency did non rise in time, power plants would close down and the filigree would brainstorm turning itself off completely. This would get out all 26 1000000 Texans who relied on the ERCOT filigree without ability for weeks or months.

A few more minutes ticked by. The frequency kept falling, touching 59.302 hertz, yet another alarming precipice. At 59.3 hertz, human operators are taken out of the equation: they are too ho-hum to brand the urgent adjustments that are needed to stabilize the grid. The system is programmed to automatically start blacking out as many areas every bit are necessary to balance power supply and demand. Only in this scenario, that fail-safe may not take worked because then many areas had already been manually cut off. "We were on the very edge," said Easton.

In a last-ditch endeavor to forestall the grid's collapse, ERCOT placed a fourth hotline call, at 1:55 a.thou., and ordered another 3,500 megawatts. All across Texas, grid operators were moving as speedily as they could, blacking out more than and more than neighborhoods, but they were running out of options. Equally the countdown approached zero, the frequency all of a sudden shot back up. The immediate crisis was over—the last-second load shed had worked—but for nearly of the post-obit day, the grid remained dangerously unstable.

Information technology is hard to fathom the destruction a full shutdown would have wreaked. Nib Magness, then the CEO of ERCOT, would explain equally much to the Texas Senate ten days later. Magness is a lawyer with a buzz cut and ramrod-straight posture who spent time in the nineties and aughts every bit a practicing Buddhist. "What my squad and the folks at the utilities in Texas would be doing is an exercise called 'blackness start,' " he said. A black beginning would have required carefully rebooting a few power plants at a fourth dimension and using them to spring-start others, thereby restoring the filigree piece by piece. It's non a thing of flipping switches. The steps required for a black starting time are numerous, complex, and delicate. No one knows how long that process would have, because no one has ever needed to practise it. Magness said it would have been weeks at least.

Most of the country's residents would have been without heat, potable water, or light, as would well-nigh all of the businesses on which they depend. Traffic lights wouldn't have worked. Caravans of trucks, likely escorted by the National Guard, would take delivered fuel to generators to proceed hospitals (many of which were nearly at max capacity because of COVID-19), burn down departments, and other emergency services operating. When the freeze lifted and the roads thawed, many would have attempted an exodus into neighboring states—all of which, with a few brief exceptions, kept power—but fifty-fifty that would have proved difficult because gas pumps run on electricity. Magness looked grimly around the Senate bedroom as he described the doomsday scenario. "Imagine: the suffering that we saw [would accept been] compounded."

In her basis-floor apartment on Uvalde Route, a busy commercial thoroughfare in the Cloverleaf community, simply east of Houston, Mary Gee liked to sit past the window, watching the people and cars passing past. Beyond the style were an motorcar-parts store, a car wash, and a Tex-Mex restaurant. At that place was always something happening. But the snow and ice in February brought Uvalde to a standstill.

The neighborhood lost power early on Monday morning, February 15. After the lord's day rose, a few neighbors ventured out. Word passed in Gee'southward complex, the Havenwood, that a nearby Burger Rex was open—that would have meant non only food merely warmth. Some decided to check it out. This wasn't an pick for Gee. She was relatively good for you, but at 84, walking more than a mile on slippery sidewalks was out of the question.

"Information technology kind of felt similar the terminate of the world," said Christion Jones, who lived a few doors downwards from Gee. Other residents sat in cars to warm upward, their engines idling, the exhaust forming pocket-sized clouds in the frigid air. But Gee had stopped driving years before and had given the concluding car she owned to a god-granddaughter.

Gee had grown up with eight brothers and sisters, and much of her childhood was spent in a rural house with a wood-called-for heater in the small town of Normangee, between Houston and Waco. She had worked every bit a nurse for more than twenty years at Houston Methodist hospital. On weekends, she and her husband, Herman, had kept a shed at a local flea market selling clothes, LPs, purses, electronics—a fiddling bit of everything. Gee liked to chat up the regulars.

Herman died in 2018, and she tragically lost her but child, Michael, the side by side year. But Gee wasn't alone. Most of her siblings had moved to Bryan and Houston, which meant she was surrounded past nieces and nephews. She often spoke with them on the phone, calls that would stretch at least half an 60 minutes as Gee asked about relatives i by one. If any were struggling, she would pray for them.

The 24-hour interval Gee lost power, her niece Zona Amerson tried to call her, simply no i picked up. Amerson, who's 64, was concerned, but there was no way to bulldoze across town to check on her. The roads were impassable. Then one of Amerson's pipes outburst, with no plumbers bachelor to fix it. She was distracted by her own crunch.

On Th, Amerson heard from a relative that her aunt had died. A Harris County medical examiner ruled that the cause was hypothermia. Gee was one of hundreds of Texans who died considering of the lack of electricity. (The country recently updated the death price to 246, a number that falls far short of the full that experts on mortality say is the true measure out of the cost in lives of this disaster, which accounts for those who, for case, had a centre attack and couldn't get to a hospital.) Others included a centenarian in a senior living community in Houston who'd as well succumbed to hypothermia; she'd received a college degree in the thirties and had taught elementary school in a single-room school in Wisconsin. An 87-year-old Austin adult female died of a fast-moving urinary tract infection later on her catheter froze. Two men in Garland are believed to have died of carbon monoxide poisoning—neighbors said they were running a gas-powered generator inside an apartment unit of measurement. In Saccharide State, southwest of Houston, a family used their fireplace to stay warm. The house defenseless fire, and a grandmother and three of her grandchildren died. The mother survived. "Almost of all, I think, what I will miss is just seeing them grow into these astonishing homo beings that I knew that they would be," she told the Houston Chronicle.

Of the millions of Texans who lost electricity during the blackouts, which lasted from Mon through Thursday, most experienced it equally a week of compounding problems. Millions either lost water or needed to boil water. When the water finally came back on, burst pipes began to flow, causing billions of dollars in damage. Plumbers were so overwhelmed with calls that some homeowners had to wait months for repairs. Economists at the Dallas Federal Reserve estimated that the blackouts cost the state'south economy somewhere in the $80 to $130 billion range, potentially making it the most expensive disaster in land history.

Of the millions of Texans who lost electricity during the blackouts, nigh experienced it as a week of compounding problems.

Fifty-fifty Texas newcomer Elon Musk, the chief executive of Tesla and the world's richest person, was affected. "I was actually in Austin for that snowstorm in a house with no electric, no lights, no power, no heating, no internet—couldn't really fifty-fifty get to a food store," he said at an investor meeting in October.

Dan Meador, an engineering manager at Austin tech firm Anaconda, besides lost ability. He and his pregnant wife bedded down in their living room in forepart of their fireplace. When they woke in the morning, it was seven degrees exterior with a windchill factor of −8. He used the burn to boil cowboy java and cook sausages in a bandage-iron pan. The following days were devoted solely to meeting basic needs: finding firewood and preparing meals. When a neighbor'southward cedar tree splintered and savage nether the weight of water ice, he fetched his chain saw—before remembering it was electric. Meador, a former linebacker for the Academy of Arkansas football team, used a hacksaw instead. When I spoke to him eight months later, he was still shaken by the experience. "You turn your water faucet on, water comes out," he said. "There's a lot of religion that we have in this stuff merely showing upwards."

The Texas Legislature was yet in the early stages of its biennial gathering in Austin when the blackouts occurred. Lawmakers and staff were told to stay off the icy roads. This appears to be the first time in state history that winter atmospheric condition forced legislators to stay home.

Of course, that didn't stop politicians from pointing fingers. Rick Perry, onetime governor and sometime U.S. secretarial assistant of energy, tried to preempt calls to increase federal oversight of the state'due south grid. In a hitting brandish of insensitivity to the families who were grieving the loss of loved ones, he claimed that Texans were willing to forgo ability "for longer than three days to keep the federal government out of their business." Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick was one of many politicians to blame wind turbines. "Our renewables aren't reliable," he said on Good Morn America. Governor Greg Abbott appeared on Sean Hannity's Trick News bear witness and argued that the blackouts showed how the Light-green New Deal, which was then a discipline of intense debate in Washington, D.C., would be a "deadly deal for the U.s.."

Blaming renewables was, of course, a politically convenient lie. Aye, some wind farms in W and South Texas had frozen up—their operators hadn't invested in blades with internal warming coils that allow windmills to office perfectly fine in other states and regions, including due north of the Arctic Circumvolve in Kingdom of norway. But many windmills kept working, helping to prevent a worse disaster. Even Abbott admitted, while the blackouts were ongoing, that the biggest culprit was ability plants that ran on gas.

Every bit the death toll climbed, the politicians' rant ebbed. Abbott added a new item to the legislative session: winterizing the country's ability arrangement. Patrick promised, "We're going to get to the lesser of this and find out what the hell happened, and we're going to fix it."

Such promises had been fabricated before. A decade earlier, in February 2011, temperatures in Texas plunged into the single digits, and ERCOT instituted rolling blackouts that afflicted 3.4 million homes and businesses (but for just a thing of hours, rather than days). David Dewhurst, a Republican who was then the lieutenant governor, blamed a lack of "winterization and grooming." Weeks later, the Legislature held a hearing on the blackouts, and Troy Fraser, a Republican state senator representing the 20-fourth District, demanded, "How are nosotros going to make sure that doesn't happen once again?"

The answer came in the class of a bill introduced by Senator Glenn Hegar, a Republican from Katy. It required the Public Utility Commission, which oversees ERCOT and the state's electricity utilities, to review power plants' weatherization plans. If whatever plan was deemed bereft, the PUC could request more detail, but it had no enforcement potency. (The bill didn't mention the need to winterize natural gas pipelines, an omission that rendered the measure effectively meaningless, since those ability plants, fifty-fifty if fully operational, can't produce electricity without a steady supply of gas.) Craig Estes, a Republican senator from Wichita Falls, tried to put some teeth on the beak with a substitute that required power plants to comply with the state's findings. Simply a few days subsequently, Hegar'due south original bill was back, with Estes'south changes stripped out. Hegar, who subsequently left the Senate and was elected state comptroller in 2014, ensured the PUC was piddling more than than a glorified paper collector.

DeAnn Walker reiterated as much when, on February 25 of final yr, the Senate business and commerce committee held a xiv-hour hearing to determine what had happened this time effectually. Walker, the chair of the PUC, testified that her agency's job was simply to get together and warehouse the plans. "I don't believe nosotros, as the PUC, have authority to require weatherization," she said.

For many of the lawmakers, the lengthy hearing was a crash course in the labyrinthine mechanics and hierarchy of the state'due south grid. The federal regime regulates all of the country's regional grids except for ERCOT, which operates wholly inside Texas. (When regional grids experience blackouts, they are able to import power from neighboring grids; considering the Texas grid is an isle unto itself, with just a few pocket-size connections to Mexico and other states, importing large amounts of power isn't an pick.) The ERCOT filigree covers almost all of Texas, though El Paso and parts of East Texas are plugged into other regional grids. ERCOT is overseen past the PUC, whose 3 commissioners are appointed by the governor. Since the 2011 freeze and blackouts, all the agency'southward commissioners take been picked past Abbott and Perry. (The PUC was later expanded to include 5 commissioners.)

A divide body, the Railroad Committee of Texas, regulates the state's oil and gas industry—or at to the lowest degree it's supposed to. In practice, it seldom does. Its iii commissioners are elected, and their campaign coffers are filled past oil and gas industry executives. Following the 2021 coma, the commissioners expressed little involvement in learning why the February storm caused statewide outages only in Texas, not in neighboring states and states far to the north. They instead aggressively defended the industry they're supposed to regulate, arguing publicly that the state's failure to require winterization of natural gas providers played no role in the disaster. At the February committee hearing, Christi Craddick, then the Railroad Commission chair, tried to pin the arraign on electric power producers, challenge that the gas industry was hamstrung by lack of electricity, not the other way around. "The oil field merely cannot run without power," she testified.

"Yes, information technology tin can happen again." That'southward what Curt Morgan, principal executive of the power visitor Vistra, told me.

That claim, yet, doesn't withstand scrutiny. Craddick was well aware of issues with the gas supply before the blackouts began, something I discovered while reviewing records of dozens of phone calls, emails, and texts among those responsible for keeping the lights on. V days before the blackouts began, Walker, the PUC chair, received an unwelcome phone call from an executive at Vistra, an Irving-based company that is the largest ability producer in ERCOT. The executive warned that the company would be unable to meet the rising need for electricity because it would soon confront natural gas shortfalls at several of its plants. Texas normally produces most 29 billion cubic feet of gas a solar day. By February xi, when temperatures hit 22 degrees in Midland, near 915 million cubic feet were already offline, according to a federal study on the blackout. (Six days later, around the peak of the blackouts, 3.vii billion cubic feet were offline. All only 591 million of that was acquired by the failure of gas infrastructure.)

That morning, Walker called Craddick. "We are going to take gas problems at our gas plants," Walker said. The next day, the Railroad Commission issued an emergency order intended to help power plants get access to gas, but the gild added to the growing defoliation. In that location was only so much natural gas to become around, and the Railroad Commission wasn't sure exactly who should get it. On Feb 13, two days before the blackouts began, 22 gas processing plants had been disrupted by common cold conditions weather. Not a unmarried ane was disrupted past loss of electric power.

Country senator Charles Schwertner, an orthopedic surgeon from Georgetown and a conservative Republican, knew piddling nearly the grid when his home's power went out that calendar week. Merely he was a quick study. A few weeks later the initial February hearing, Lieutenant Governor Patrick asked him to bear the main bill to ready the grid. Schwertner later told me he concluded correct away that the PUC commissioners were "derelict" in their oversight duties.

I met him in his Capitol function, which is adorned with prints of the Battle of Gettysburg and the Confederate assail on Fort Sumter. He was proud of the bill he wrote. Information technology created a regime trunk to ensure coordination between the gas and power industries. (As reliant every bit these industries are upon each other, no such formal body had existed before.) The beak directed the PUC and the Railroad Commission to levy a $ane million fine each day on power plants, pipelines, and natural gas facilities that failed to winterize, and it allocated an initial $21 million to the Railroad Committee to hire well-nigh a hundred inspectors to verify that the gas industry was preparing for cold weather.

When Schwertner sent his pecker to the House, the legislation likewise created a committee to map the gas-electric supply chain and decide which gas facilities were critical to the functioning of power plants. It authorized the Railroad Commission to use its hundred new employees to inspect and, if necessary, fine gas companies. When the bill returned from the House, though, the language had been revised: only companies "prepared to operate during a weather emergency" were considered critical. This created a troubling loophole. Once the bill had passed, the Railroad Commission was responsible for implementing it, and the bureau proposed a rule allowing gas companies to exempt themselves from winterizing merely by paying a $150 filing fee and claiming that a facility wasn't prepared to stay operational—a dizzying bit of circular reasoning.

Schwertner told me that requiring winterization for one part of the filigree (the electric power providers) but non another (those who provide gas to the electricity providers) reflected the political power of the gas industry. "There was some pushback by industry," he said, citing natural gas producers and pipeline operators. He said he didn't like the House changes, specially the weakening of "weatherization requirements of natural gas." Some of his colleagues were less diplomatic.

During a Senate committee hearing in September, Lois Kolkhorst, a Republican senator from Brenham, reamed out Railroad Commission executive director Wei Wang for not finer implementing the law. Kolkhorst chosen the $150 opt-out fee "agonizing." At the same hearing, Senator John Whitmire, a Houston Democrat, offered Wang a compliment of sorts. "You've unified this body—let me just cheers for that. Yous've brought the family together here . . . Your rule-making proposal sucks." Schwertner wrapped up the conversation by demanding change.

The Railroad Commission didn't budge, and it was roundly condemned. Then, in late Nov, it appeared to opposite form, at to the lowest degree rhetorically. Information technology announced that most pipelines and gas processing plants, along with many wells, would be required to winterize. But thus far the commission has engaged in delay tactics. These rules won't be finalized until onetime afterward this year—after the winter. Perhaps the rules will be potent enough to compel real change. But if past is prologue, the new rules are likely to be ineffectual—a repeat of what happened in 2011.

The week of the blackout produced staggering, hard-to-fathom free energy bills Texans will be paying for years. That'south because the state's electricity market broke former around midday on Monday, Feb fifteen. In the hours after the blackouts, ERCOT tried to shore up electricity reserves to stabilize the filigree. The figurer organization that runs the market, though, interpreted this every bit an oversupply (in the middle of blackouts!) and dropped prices. When ERCOT and the PUC realized what was happening, officials decided to bypass the market and, on Monday evening, manually set up prices at the maximum of $9,000 per megawatt hr. (Past comparison, the average hourly toll in 2020 was $25.73.) For fear that restarting the market and letting prices fluctuate in the midst of blackouts would lead to instability, officials kept prices at that artificially inflated level until Friday.

Equally a result, Texans spent an exorbitant amount on electricity during a calendar week in which nigh of them couldn't get much electricity. For the entirety of 2020, Texans paid $ix.8 billion to keep the juice flowing. On February xvi solitary, they spent roughly $ten.3 billion. Costs for the month of Feb totaled more than than $fifty billion.

The beak for this pricing disaster is coming due. The Legislature canonical the issuance of what volition likely end upwardly being about $5 to $6 billion in bonds to pay back some of these costs. That class of borrowing creates an obligation of almost $200 for every developed and child in Texas.

Of the ii,500 participants in the ERCOT marketplace—power plant owners, electricity marketers, electric cooperatives, creditors, and traders—many are privately held and don't disclose their profits and losses. Just some of the big shareholder-endemic electricity generators were stuck with major losses because, while electricity prices were astronomical, natural gas prices were even higher.

As a result, anyone who had natural gas to sell came away a winner. Large Dallas-based pipeline owner Energy Transfer posted a net profit of $3.29 billion for the get-go three months of 2021; it had never posted even a $1 billion quarterly margin before. The company chalked up its profits to grooming—it had forked over the money to winterize parts of its facilities, so they remained up and running during the storm. Kinder Morgan fabricated $i.41 billion, its best quarter always. British oil giant BP, which supplies more than gas in the U.S. than any other company, was coy. "It was a very exceptional quarter in gas trading," CEO Bernard Looney told Bloomberg, which pointed to an guess suggesting that the firm reaped $i billion during that stretch. Gas producer Comstock Resources president Roland Burns put it much more plainly, saying it was "like hitting the jackpot."

Co-ordinate to Bloomberg, about $8.1 billion was spent on gas burned to generate electricity during that week. Another $3.iii billion went for gas sold straight to homeowners, a figure that's publicly available only because the Railroad Commission approved the issuance of bonds to compensate iii gas utilities that paid exorbitant prices for fuel that week. These bonds will be paid off through extra charges on customers' monthly bills, though it'south non even so clear for how long. Even more was spent by city-owned gas companies, many of which take tacked on additional charges to customers' bills to pay off the enormous costs the companies ran upward over a few days.

It's possible that some of the massive profits made by gas companies were illicit. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is looking into potential market place manipulation by Texas pipeline companies, which are bailiwick to the to the lowest degree regulation and oversight of any pipelines in the country. Those companies operate in a regulatory penumbra. For their pipelines operating simply in Texas, they're generally exempt from reporting tariffs and other market information the federal government requires of interstate pipelines. This makes it difficult to decide whether gas prices were manipulated. In September, FERC chair Richard Glick told Congress, "Nosotros have found a number of anomalies." FERC afterwards disclosed that two cases of possible natural gas marketplace manipulation were beingness investigated, though it wouldn't identify the two companies involved. (Disclosure: Texas Monthly's chairman is Randa Duncan Williams, who is also chairman of the general partner of Enterprise Products Partners, a major pipeline company whose gas pipelines are located entirely within Texas. Company executives say they've received no inquiries from FERC.)

At the same September hearing, Kansas senator Roger Marshall asked a panel of FERC commissioners, "Was there price gouging, and who made the coin?" None of the iv commissioners came upward with an answer.

Most Texas politicians accept shown piffling interest in fifty-fifty asking this question. The chief executive of every major power plant in Texas testified repeatedly earlier state lawmakers. But Kelcy Warren, the chair of Energy Transfer, never appeared. Warren and so gave a $ane one thousand thousand campaign contribution to Abbott on June 23, shortly after the legislative session concluded—a session in which Abbott, despite his initial calls to ready the filigree, resisted muscular new regulation of the gas industry. (Oil and gas executives, employees, and political activeness committees contributed about $16.half dozen million of the $79 1000000 that Abbott raised from 2017 through 2020, according to an analysis by Texans for Public Justice.)

For his function, Texas attorney general Ken Paxton, who'southward awaiting trial on felony securities fraud charges, hasn't appear that his function is investigating any free energy cost gouging. I recently asked PUC chair Peter Lake, whom Abbott appointed in the spring, subsequently DeAnn Walker resigned, to assess who profited from the disaster. "I'k non sure anybody has a full movie of the complexity of all these financial transactions," he said charily. It's telling that Lake, who was supposedly brought in to prepare ERCOT and the electricity market, dodged a question nigh who stood to gain and lose the almost from maintaining the status quo.

Though it may be hard to believe today, Texas's grid became a pioneer in the earth of electricity generation and distribution 2 decades agone.

The most prominent Texan who appears to be itching for a confrontation with gas companies is Paula Gold-Williams, the longtime head of CPS Energy, the city-endemic utility in San Antonio. Days after the crunch ended, two gas suppliers owned past Energy Transfer sent CPS an email asking for $317.5 million. "Due to the unprecedented weather event over the past 10 days, the price of natural gas rose dramatically," the email said. Information technology demanded that CPS pay cash or provide a letter of credit.

CPS refused to pay. Instead, information technology filed a lawsuit claiming price gouging. In its downtown San Antonio offices, Gilt-Williams had watched electricity and gas prices advisedly earlier and during the debacle. A native of San Antonio'due south Eastward Side, she trained as an auditor and worked every bit a regional controller for Fourth dimension Warner and as a vice president at Luby's earlier joining CPS, where she worked her way up to CEO. "We will pay every legitimate cost and cost," she promised, simply not a dollar more. Working with her staff, she adamant that about $40 per unit of gas was reasonable. Annihilation above that? The $500 price Free energy Transfer had demanded? That was unconscionable. When I reached out to Energy Transfer well-nigh the financial tug-of-war, the company sent a statement saying CPS was responsible for the costs because it didn't set up for the tempest. "CPS is trying to play politics and place blame on others," the statement said.

Merely when I talked to Golden-Williams, she was resolute. "I am absolutely focused on getting to the bottom of this," she said. In October, she announced her retirement, only she promised to stay engaged with the company—specifically to assist with the lawsuit.

Yes, it can happen again." That's what Brusque Morgan, master executive of the power visitor Vistra, told me when I asked near the potential for another electricity crunch. Vistra lost near $2 billion during the storm, and it plans to spend more than than $80 million by the end of this year to set its plants for the next Chill blast.

In November, I visited i of those plants, in Odessa. During the February storm, ice had accumulated and clogged the air-intake system, so Vistra is investing $2.five million to make sure that doesn't happen again. From atop any of the plant's four 10-story boilers, which produce the high-pressure steam that's converted into electricity, you could await out toward the horizon and run across a landscape dotted with pipelines, pump jacks, and flare stacks. The irony was stark: the institute sits in the heart of ane of the world'south largest oil and gas fields, even so when blanketed past extreme temperatures, it couldn't get the gas it needed to stay operational.

Though Vistra is ensuring its own plant volition be able to sustain such conditions, the same tin't exist said for its neighboring gas producers, which means its own investment may be futile. "I worry about the gas organisation," Morgan told me. "The expanse that I'k almost concerned near is the Railroad Committee oversight." He'south not lonely.

You lot might recall that the natural gas manufacture, having scored a multibillion-dollar windfall at the expense of other Texans, might show some magnanimity in victory and concord to accept steps to ensure against futurity blackouts. Only y'all would exist wrong. The gas industry continues to fight ferociously to avoid the kinds of regulations that are commonplace in other states. It has boosted by millions of dollars its campaign contributions to friendly politicians, including the three officials leading the Railroad Commission.

Meanwhile, Governor Abbott promised in November that "everything that needed to exist done was done to fix the power filigree." The Texas Tribune reported that in December, after the blackouts became an upshot in his reelection entrada, Abbott went a step further past enlisting officials at ERCOT and the PUC to launch an optimistic public relations offensive. Just when I interviewed well-nigh a dozen experts in natural gas and electricity, the consensus was that petty has been done to secure our electric grid. ERCOT itself has admitted we could face blackouts this winter. Just before the new year, the bureau released a report in which information technology suggested information technology had enough power generation to easily manage "normal" wintertime weather. Doug Lewin, an Austin-based energy consultant, blasted this conclusion on Twitter: "To say nosotros have enough ability in normal weather is not helpful."

Days later, on Jan 2, a cold front passed through West Texas. The temperature in Midland hit a low of 14 degrees before rebounding to 56 the next day. During that brief spell, the gas infrastructure faltered, with production falling past 25 percent, according to market intelligence firm S&P Global. Even so, the approach of our governor and legislators and regulators boils down to hoping we don't run across extreme temperatures anytime soon.

Indeed, forecasters predicted a relatively warm winter this yr. Some might reason that if the planet is warming, Arctic storms are less likely. There is growing evidence, however, that the opposite is true. Judah Cohen, a visiting scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Applied science, has published two influential papers on the topic, the offset in 2018 and some other this past September. The second paper, which appeared in Scientific discipline, a prestigious peer-reviewed publication, explained that as the earth warms, conditions are occurring more frequently that enable a smash of Arctic air to push far into North America, even all the way downwards to Texas. In other words, the overall warming of the planet disrupts conditions systems in ways that increase the chances for occasional extreme-cold events.

Cohen told me it all has to do with the polar vortex, an atmospheric river that circles around the Chill at an average of 90 miles an hour. Typically, it traps the cold air in the far northern latitudes, but every bit Arctic Sea ice melts and the globe warms, the polar vortex is more likely to wobble and stretch. In January and Feb of 2021, a warm mass of air from Eurasia banged into the vortex, causing it to dip southward and push cold air as far downward as the Rio Grande Valley. "Where the polar vortex goes, and so goes the cold air," Cohen explained.

And so what would it cost to winterize all the wells in Texas, equally most other states do, and ensure the electricity flows the side by side time an Arctic blast hits the Lone Star State? Dallas Federal Reserve economists cite a 2011 estimate that it would cost each gas ability constitute $50,000 to $500,000 to winterize. Statewide, it would cost between $85 and $200 one thousand thousand annually—the rough equivalent of 1 or ii days of revenue from the Texas gas industry, and less than one-fiftieth the price that the industry charged during the Feb disaster.

It's worth noting that much of the cost of winterization would remain in the Texas economy. I of the world's leading manufacturers of estrus-tracing equipment, Thermon Grouping Holdings, is based in Austin and operates a major factory in San Marcos. A few years ago, it winterized an oil circuitous on Russian federation's Sakhalin Island—where the average depression temperature in January is iii degrees Fahrenheit—for $12 million. "All of this engineering science exists," said Thermon CEO Bruce Thames. "We just haven't invested in it in the land of Texas."

This is particularly shameful to hear for anyone versed in Texas'southward history as an energy leader.

Though information technology may be difficult to believe today, Texas'due south grid became a pioneer in the world of electricity generation and distribution two decades agone. Under Governor Perry, Texas spent $6.9 billion on an ambitious programme to build iii,600 miles of new high-voltage manual lines. One set of lines stretched from Dallas to the Panhandle, forming a looping effigy that came to be known colloquially equally "the horsehead." Other lines began in Cardinal Texas and headed west, reaching toward Midland and Odessa and into the windy counties where the Chihuahuan Desert meets the Great Plains. In other states, the construction of comparable transmission lines oftentimes gets delayed for years, mired in bureaucratic morasses and landowner lawsuits. Texas completed its unabridged network in a relatively brisk nine years.

These lines were a benefaction to renewable energy developers, connecting the large population centers along Interstate 35 (and due east to Houston) to western parts of the land, where land is cheap, landowners are welcoming, and air current and dominicus are plentiful. In 2020 Texas generated more renewable electricity than whatever other state by far. California was a afar 2d. By all accounts, Texas, long famed for existence a global powerhouse in oil and gas, had cemented its leadership in the next generation of free energy.

And then came the Feb blackouts. Our folly was laid bare: it'south as if we'd built a powerful, expensive car and then tried to compression pennies by not buying antifreeze for it.

Despite this embarrassment, Texas still enjoys unmatched expertise in energy technology, financing, and manufacturing. Some of the technology and gear adult to frack oil and gas is now being repurposed to tap renewable free energy. Shipyards that once made vessels to install offshore oil rigs are now adapting for offshore wind turbines. Taking advantage of these resources would create tens of thousands of good jobs, including for workers displaced every bit oil and gas exploration inevitably declines.

Depression-carbon grids are the future, and Texas has a multiyear head start. But earlier this opportunity can be grasped, the country needs political leaders and regulators who are focused on the jobs and well-beingness of average Texans rather than on the narrower incumbent interests of owners and executives of fossil fuel companies.

This article originally appeared in the December 2021 consequence ofTexas Monthlywith the headline "It Could Happen Again." Subscribe today .

rexroadafteptips64.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.texasmonthly.com/news-politics/texas-electric-grid-failure-warm-up/

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Lets Go Burn Down the Observatory So Thatll Never Happen Again"

Posting Komentar